"In all of this, Job did not sin..."

I've come to think of these as some of the most comforting words in all of the Bible. How so? I'm glad you asked!

As a matter of review, the story of Job is given to us as an example of how a godly man may live through suffering. Job is a rich man, who has cultivated his great wealth and raised a large family, only to see it come crashing down around him. Then, he finds himself afflicted with boils all over his skin, his wife encourages him to end it all, and we see him sitting in ashes and scraping his sore, itching wounds.

Of course, we the readers get a window into the apocryphal gamesmanship between God and Satan. But Job doesn't have that privilege of perspective. He is simply living his life's story, pursuing God in what he does, then bam! Suffering! All he has left is a wife who counsels him to curse God.

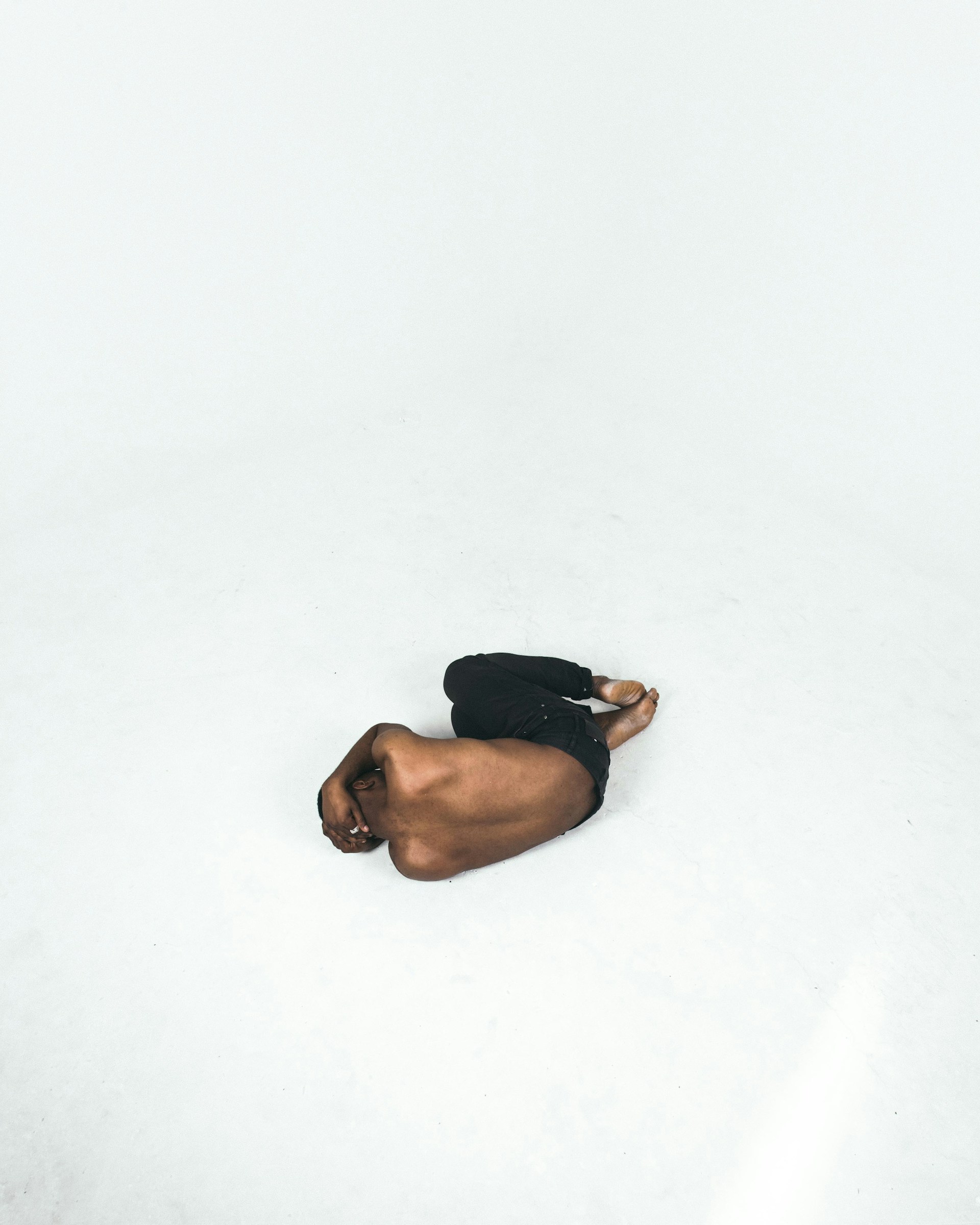

We sometimes get this picture of Job in our minds as a stoic sufferer. In other words, he might say, "Woe is me," but he must be denying himself the feeling of what must be a terrifying cluster of emotions. We can have this idea that it's just not godly to leave room for negative emotions while also following God.

I don't buy that for a minute - you don't lose what he lost without being psychologically devastated. When trauma happens, the body reacts - the body remembers many things that we shove down below the conscious level. We were not designed to serenely absorb trauma. It's not healthy to just keep it down there. Like shaking a bottle of soda, the pressure will come out eventually!

We could also think that Job just didn't care enough about his children or his possessions. That's not fair to him, though. Job wasn't on Prozac. He had followed after God, it seems, as best as he knew how. But now, out of the blue from his perspective, God's blessing had turned into a curse that wiped out everything he knew.

So... stoic? not so much. We also get a perspective from Job's friends that his response is at least naive, if not sinful itself. They would have us think that Job somehow deserved his fate - that instead of hunkering down in the ashes, he should be going on a sin hunt in his heart to find a way to repent.

The fog is filled with people who are at least something like Job. We may not have the riches to lose. We may not be separated from all of our loved ones in a single day. Job's story is certainly an extreme, but many of us do experience suffering in this broken world. Suffering that, when we are attempting to pursue God and allow him to order our steps, seems, well, pointless.

Now, I won't say that the same God/Satan chess match is happening with us, per se. But many of us do still have this inkling in the back of our minds, that we need to be hunting down the sin in our hearts. "God wouldn't let us continue suffering from this anxiety, or this depression," we think to ourselves, "if our heart was truly right with Him." And so we continue the same line of thought as the friends of Job - they thought it was wholly impossible to a) be righteous and b) be suffering.

With our New Testament hats on, we can take the cognitive dissonance a step further. We can take Job in his worst place, and place that next to Paul's admonishment to rejoice in the Lord always. I mean, he said it twice, so it must of first-order importance, right? We can point to that, then, as the smoking gun in our hearts, that we do not in fact experience joyful exuberance no matter the circumstance. For those of us who experience depression with that lack of energy, we get the double whammy that makes us feel our suffering as sinful.

So when we're going through those tough times, we can almost feel "unclean." In Old Testament Israel, to be unclean meant you had to be separated for a period of time, then sacrifice needed to be made. Things that made you unclean were not always sin-related - sometimes it was just life. We can feel that - our suffering, we feel, makes us a burden to those around us, and we ought to separate ourselves for a while until we have some resolution. That is, until we can bring joy back and be a positive influence.

I think that's why we get the picture of Job as the stoic sufferer. If we must always react with joyful exuberance no matter the circumstance, in denial of the ways that our bodies viscerally react to those circumstances, and if Job allowed himself to feel the gut-wrenching loss that he experienced, then Job most certainly did sin. But the text says he did not sin, in all of his reaction to such a terrible loss. And to think that a godly man was so disconnected from the people around him so as to not feel - well, that beggars belief. So our understanding of Paul on this point must be askew.

Now, most of us would acknowledge that in times of trauma, the psyche needs space and grace to recover. Wounds need time and care to heal. Placing undue expectations on that traumatized psyche before the recovery is inhumane and harmful. But we seem to expect everyone to "get back to business" after a while.

Recovery is allowed, it seems, as long as the sufferer progresses to a certain plateau of function. But in the fog, we seem to linger in and around that plateau. Our bodies and our minds may remain rigid or in a broken state that precludes full function and thriving in this world. And we often may wonder how we can properly pursue God in that state.

We find ourselves pleading with God to restore what is broken, to let us feel the joy that could be. And regularly, the energy just isn't there, or the anxiety that we hold in our bodies overwhelms us, or our thought processes do not seem to progress clearly.

And we like progress, don't we? We sit with our church groups, discipleship, and others, sharing our prayer requests. In most things, we expect that a resolution will come. We hope for healing, we pray for restoration, we trust God's wisdom. And then we have requests that hit the walls. The family member who isn't going to make it. The foster child we can't keep. The chronic pain that won't heal.

We can live through situations of ongoing trauma, we carry the experience and memory of brokenness in our bodies and minds, and we fail to keep the battle strong. Job had that too - his body broken, he sat in the dust. So distraught he was over his circumstances, when his sanctimonious friends came to tell him what for, even they sat with him for several days without saying a single word.

The story of Job certainly tells us that we don't have to understand our suffering and that we should not accuse God of doing wrong. But more than that, it opens room for our response. We don't have to condemn every visceral reaction as a sign of doubt. When continual traumatic experience lands us in a cycle of depression, where our bodies are failing to respond, we have room to know that isn't sinful.

We have room, as Jesus did, to weep for what we see around us. We have room to acknowledge the weakness and damaged creation that is part of every one of us. We do not have to prove something to God, or show ourselves most worthy in the midst of unconscionable circumstances.

Instead, we can feel freedom to not draw solid lines between sin and suffering. In that mode and space, God meets us to share the suffering without the pressure. We do not need to change our experience to be accepted.

References:

- Photo by Mwangi Gatheca on Unsplash

Leave a comment in response to the post: